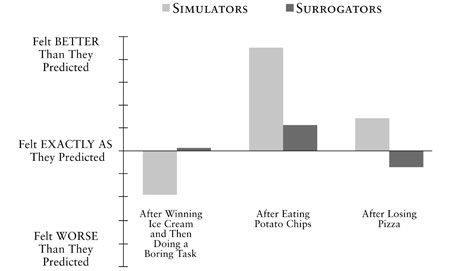

When it comes to making decisions, the imagination has been virtually our only option throughout human history. It’s such a deeply ingrained process that we likely never even think about an alternative. When making decisions, people imagine how they’ll feel once they’ve made the decision. If they imagine that the decision is worth doing, they may pursue it. But we have shown that the imagination does an awful job of simulating what the future will feel like for all kinds of reasons. In one-on-one studies surrogation not only produces far more accurate results than imagination, it also avoids each of the pitfalls that make the imagination such an unreliable method of decision-making. So why aren’t we all using surrogation? Well, there aren’t many people who know about it yet. What’s troubling is that many of the people who have been made aware of the superiority of surrogation have stuck with imagination. Why are these people choosing a lesser option? What’s the deal with surrogation skepticism?

In Stumbling on Happiness, Daniel Gilbert pinpoints the reason behind people’s reluctance to adopt a clearly superior decision-making method. People tend to overestimate how unique they are. People believe that they are fundamentally different from other people. As a result, they think that the experiences of strangers don’t necessarily apply to them. So they keep on imagining and keep on making poor decisions.

“Science has given us a lot of facts about the average person, and one of the most reliable of these facts is that the average person doesn’t see herself as average. Most students see themselves as more intelligent than the average student, most business managers see themselves as more competent than the average business manager, and most football players see themselves as having better “football sense” than their teammates. Ninety percent of motorists consider themselves to be safer-than-average drivers, and 94 percent of college professors consider themselves to be better-than-average teachers. Ironically, the bias toward seeing ourselves as better than average causes us to see ourselves as less biased than average too.”

We may be inclined to rate ourselves as better than average, but it isn’t that simple.

“When people are asked about generosity, they claim to perform a greater number of generous acts than others do; but when they are asked about selfishness, they claim to perform a greater number of selfish acts than others do. When people are asked about their ability to perform an easy task, such as driving a car or riding a bike, they rate themselves as better than others; but when they are asked about their ability to perform a difficult task, such as juggling or playing chess, they rate themselves as worse than others.”

Gilbert cites three reasons for why we think we’re special.

- The way we know ourselves is completely unique. We experience our personal thoughts and feelings constantly. If you compare the experience of being a self and the experience of interacting with other people, it makes sense that we would overestimate our uniqueness.

- Feeling unique feels good. While we enjoy relating to people, we don’t like feeling too similar to other people. He provides the example of someone’s night being ruined by seeing another person with the exact same outfit at a party.

- We overestimate everyone’s uniqueness. In our social lives we select the people we associate with by distinguishing valued traits. “Individual similarities are vast, but we don’t care much about them because they don’t help us do what we are here on earth to do, namely, distinguish Jack from Jill and Jill from Jennifer… Because we spend so much time searching for, attending to, thinking about, and remembering these differences, we tend to overestimate their magnitude and frequency, and thus end up thinking of people as more varied than they actually are.”

The moral of the story is that the handful of people that have rejected surrogation have done so on false grounds. It’s ironic that people seem to be wary of basing decisions on the experience of strangers since we’ve shown how the imagination makes us strangers to ourselves.The experience of strangers might seem like they aren’t applicable to you but the results can’t be ignored.

Gilbert seems to think the results can and have been ignored. He concludes his book with a tone of resignation. One of his last sections is called “Rejecting the Solution”. His final two sentences say, “There is no simple formula for finding happiness. But if our great big brains do not allow us to go surefootedly into our futures, they at least allow us to understand what makes us stumble.” In other words, at least we can become aware that the imagination is preventing us from making good decisions even if we refuse to do anything about it.

Next time we’ll look at how Sentio Search will make people want to make the change and embrace the solution of surrogation.